If you were to ask me to summarize everything we have learned from the learning sciences over the past 40 years, and to identify the single most important lesson for the clinical research community to embrace, it would be this: passive, didactic, traditional learning experiences rarely lead to learning. Let this sink in—most of what we develop and deliver when training clinical trial staff and teams, has been proven largely ineffective.

Making matters even worse, in study after study after study, adult learners wholeheartedly believe that passive, didactic, traditional learning experiences are effective learning experiences. This is what they prefer, even after being shown the ineffective outcomes of the training. And when trainers build their training, and they evaluate their training outcomes through satisfaction surveys, they feel rightly justified in continuing to present the same formats that the evidence demonstrates don’t work. The impact of this disconnect can not be understated.

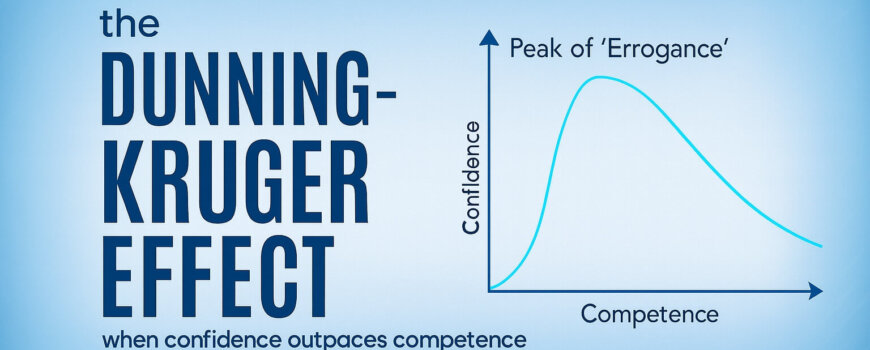

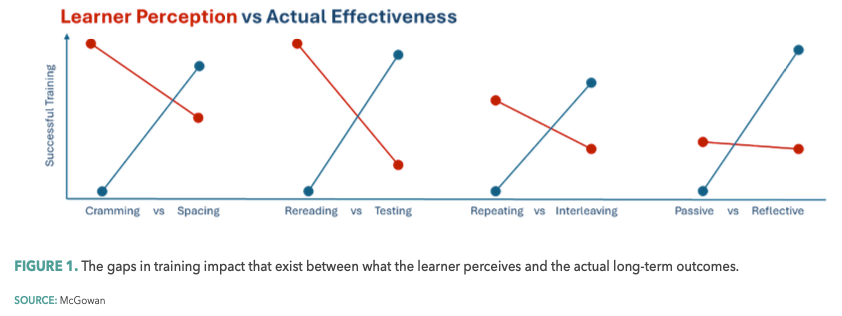

In this article, I’d like to introduce the science and the opportunities of leveraging “desirable difficulties” in training. Originally introduced by UCLA’s Robert A. Bjork more than 30 years ago,1 the concept of desirable difficulties suggests that learning experiences that are initially challenging significantly enhance long-term retention and mastery of skills, but trainees unknowingly perceive just the opposite being true…creating a chasm between what learners prefer, and what actually works (see Figure 1).

Desirable difficulties: A cognitive bias in learning

Desirable difficulties are learning experiences that require reflective effort, making them seem challenging in the short term yet beneficial for long-term learning and performance. Examples include varied practice conditions, spacing learning sessions over time, generating reflection through behaviorally designed learning moments, and embracing testing as a critical learning tool rather than merely as a means of measuring (judging) learners.

To understand the root disconnect of desirable difficulties we must acknowledge the work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky who demonstrated that we (adult humans) are routinely victims of cognitive biases and fast and slow thinking.2 Kahneman/Tversky highlight how our intuition (fast thinking) often leads us to prefer simple or familiar strategies. However, in learning, these comfortable strategies, unlike more effortful strategies, are far less effective.

In research more specific to clinician learning, David Davis’ exploration of clinician self-assessment highlighted a related challenge: clinicians overestimate their abilities and learning needs.3

The integration of desirable difficulties can also help correct these misjudgments by providing feedback that is more aligned with actual performance, thus fostering better self-awareness and more targeted learning.

Four strategies for implementing desirable difficulties in training

One of the main challenges with embracing desirable difficulties in training is the initial perception that these methods are less effective because they make learning feel harder.

This perception can discourage learners and educators alike. However, research is conclusive—while performance may initially seem more challenging, long-term retention and the ability to apply knowledge and skills are significantly improved.

To effectively implement desirable difficulties in clinical research-related training, consider the following strategies:

- Interleaved practice. Instead of focusing on one topic at a time, mix different subjects within a learning experience. This approach helps learners better discriminate between concepts and to apply knowledge appropriately in practice.4

- Spacing effect. Distribute learning experiences over time rather than combining them into a singular prolonged session. This strategy enhances memory consolidation and recall.5

- Testing as learning. Use frequent low-stakes testing not just to assess, but as a tool to strengthen memory and identify areas needing improvement. Leverage pre-tests to shape learning and utilize reflective poll questions throughout the training experiences.6

- Engineer reflective learning moments. Learners repeatedly default to low attention, low reflection states while learning. Creating a consistent rhythm of “nudges” that drive reflection can lead to four to six times greater learning and retention.7

Realizing the impact

If your goal is to effectively train and prepare staff and sites to successfully execute your drug development studies, incorporating desirable difficulties into clinical research-related training is not optional—it is how effective learning happens. More than 30 years of research evidence supports the effectiveness of desirable difficulties in enhancing professional knowledge, competence, and skill; and it is increasingly being embraced by our partners, including pharmaceutical company sponsors and contract research organizations, in their trial-related training.

By challenging ourselves to embrace these “difficulties,” we will find that things actually get a whole lot easier.

Brian S. McGowan, PhD, FACEHP, is Chief Learning Officer and Co-Founder at ArcheMedX, Inc.

References

1. Bjork, R.A. Memory and Metamemory Considerations in the Training of Human Beings. Metcalfe, J.; and Shimamura, A. (Eds.). 1994. Metacognition: Knowing about Knowing (pp. 185-205). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1QS48Q9Sg07k20uTPd3pjduswwHqTj9DD/view?pli=1

2. Kahneman, D. (Author); Egan, P. (Narrator). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Random House Audio. 2011. http://www.bit.ly/3zXJdZi

3. Davis, D.A.; Mazmanian, P.E.; Fordis, M.; et al. Accuracy of Physician Self-Assessment Compared With Observed Measures of Competence. JAMA. 2006. 296 (9), 1094-1102. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cMBpFDUNVr74dNdfgFzdq7ENcfQVahcY/view

4. Van Hoof, T.J.; Sumeracki, M.A.; Madan, C.R. Science of Learning Strategy Series: Article 3, Interleaving. JCEHP. 2022. 42 (4), 265-268. https://drive.google.com/file/d/18Jd14COH0UfQ5c4TJcb-DCBrHKy5pLgy/view

5. Van Hoof, T.J.; Sumeracki, M.A.; Madan, C.R. Science of Learning Strategy Series: Article 1, Distributed Practice. JCEHP. 2021. 41 (1), 59-62. https://drive.google.com/file/d/18MZnQcaZd8Yfi_dRPkpYliuElONZcju3/view

6. Van Hoof, T.J.; Sumeracki, M.A.; Madan, C.R. Science of Learning Strategy Series: Article 2, Retrieval Practice. JCEHP. 2021. 41 (2), 119-123. https://drive.google.com/file/d/18MVcNHOtL8Pfj1V7xYHgINkyl0dsfwC2/view

7. Alliance Almanac. The Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions. December 2014. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gTej_TiOLxSsZoB58MI6x-S7wPEOJJQA/view